Update: Please see the note below the blog-post.

I had written previously about [the difficulty of] choosing a Physics textbook for an independent high schooler. I am pleased to report that the book by the Physical Sciences Study Committee was well-received by Rujuta. However, it was also a challenge. I am not exactly sure if I was able to create a lasting love for Physics in her. Perhaps I should have followed Bruce Yeany’s YouTube channel more; we should have done more experiments. I will correct that mistake for Chemistry, about which I will write later.

Steaching science is a humbling experience. Steaching math, in my experience, has been slightly easier. Perhaps mathematical concepts are easier to demonstrate. Indeed, the great mathematician Vladimir Arnold maintained that Mathematics was a branch of Physics1.

As a student becomes a high schooler, they encounter calculus, specifically the calculus of variations. Much has been written about how to introduce calculus to high schoolers. I believe that the study of precalculus, where one should fall in love with functions, is a prerequisite to the study of calculus. Rujuta did her precalculus last year and did well on the AP-precalculus test. She showed interest in understanding functions. Whenever we understood and plotted polynomial, rational, exponential, logarithmic, periodic, and trigonometric functions (and some weird and beautiful ones like the folium of Descartes), her eyes used to light up. There used to be occasional memory lapses, but since she was accustomed to reconstructing results from first principles, problem-solving was fun. Guessing the shape of functions first, predicting their asymptotes on a coordinate plane, and then validating the predictions using amazing tools like Desmos or GeoGebra was priceless.

I had imagined that as she (or a student like her who enjoyed mathematics, solved problems reasonably well, and approached it playfully, if somewhat apprehensively) entered the 11th grade, I would need to introduce her to calculus, the apparent bridge between elementary mathematics and higher mathematics.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t subscribe to such a ranking in mathematics. Great masters like Israel Gelfand, Heinrich Dorrie, Hugo Steinhaus, A. R. Rao, John Conway, and Martin Gardner (to name only a few) have written much about deep mathematics without ever mentioning calculus. Understanding that elementary mathematics and plane geometry alone are enough for a lifetime.

However, we should accept the foundational place of calculus in studying mathematics for college and solving practical engineering problems2. After all, we have asked intriguing questions related to such smooth geometrical shapes as the circle, parabola, ellipse, hyperbola, and so on since the time of Archimedes.

Since Newton, who, along with Leibniz, formulated one way of looking at calculus, things have only become more intense, more demanding. For centuries, since its formal introduction in the seventeenth century, despite challenges of its mathematical rigor, calculus has been immensely useful in solving practical problems and analyzing natural phenomena.

My main concern was about a good introductory textbook, however! The Internet (including ChatGPT, Gemini, etc.) has several suggestions. There are drills and scrolls of problems. There are research council recommendations. There are books, many of which are good, even great.

Introducing calculus to impressionable, creative, if somewhat diffident, youth3 has been a challenge for generations! Believe me, many great professors and teachers have spent countless hours choosing the right kind of introduction to calculus. Results have been mixed. I, a computer science graduate and professional computer programmer, spent last summer thinking and exploring this topic.

We tend to rely on our beliefs when faced with such bewildering questions whose answers are not just a few Internet searches away. Martin Gardner holds a high place in my mind when I think of master expositors of mathematical ideas. I might write about Martin separately, but, for now, it suffices to say that if Martin had suggested to me what to do in a dream, I’d have accepted it.

That’s silly, of course. But if Martin, or someone like him, makes a compelling case for a Calculus-1 text, then how can one ignore it? I was fortunate to find Calculus Made Easy by Silvanus Thompson, with a preface by Martin Gardner.

Here is what Martin writes (emphasis mine) in his beautifully written preface about this book. He also draws our attention to the fact that a lively introduction to calculus has been a source of concern for decades:

The American philosopher and psychologist William James, in an 1893 letter to Theodore Flournoy, a Geneva psychologist, asked “Can you name me any simple book on the differential calculus which gives an insight into the philosophy of the subject?”

…

In spite of the current turmoil over fresh ways to teach calculus, I know of no book that so well meets James’s request as the book you are now holding. Many similar efforts have been made, with such titles as Calculus for the Practical Man, The ABC of Calculus, What Is Calculus About?, Calculus the Easy Way, and Simplified Calculus. They tend to be either too elementary, or too advanced. Thompson strikes a happy medium. It is true that his book is old-fashioned, intuitive, and traditionally oriented. Yet no author has written about calculus with greater clarity and humor. Thompson not only explains the “philosophy of the subject,” he also teaches his readers how to differentiate and integrate simple functions.

…

Many of today’s eminent mathematicians and scientists first

learned calculus from Thompson’s book. Morris Kline, himself

the author of a massive work on calculus, always recommended it

as the best book to give a high school student who wants to learn

calculus. The late economist and statistician Julian Simon, sent

me his paper, not yet published, titled “Why Johnnies (and

Maybe You) Hate Math and Statistics.” It contains high praise for

Thompson’s book.

In that preface, Martin outlines his reasoning. The book has had three editions4; the last one (which featured Martin’s preface above) was published in 1998.

We have been studying from this book for a couple of months, and it has been a wonderful experience. Thompson’s style is direct and devoid of any pomp. At times, he seems to scathingly criticize mathematicians, but it is more of a reaction to the pedantic teachers who may have prevailed at the time he wrote the book in the late 19th century.

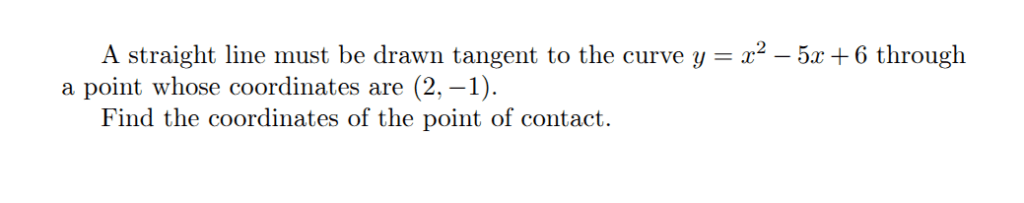

What I like the most about the book is its correctness (that is what one expects from a book that has been thoroughly edited), humor5, and forthrightness. He does not water down the material, but also doesn’t want us to unnecessarily belittle ourselves in front of the grandiose edifice of mathematics. Careful reasoning is our companion throughout. So far, I haven’t found a single typo in the book. Discussion is lively, problems are beautifully composed. Here is a problem that Rujuta had great fun solving:

It is impossible to teach mathematics without its history. This is especially true about Calculus, which is riddled with subtle issues–including the befuddling Zeno’s paradoxes6, Ancient Greeks’ (including Archimedes) omission of the infinitesimal, Newton’s and Leibniz’s Midas touches, George Berkeley’s criticisms of the infinitely small and the infinitely close, Weierstrass’s reformulation using limits (which banished the infinitesimals temporarily from calculus and analysis7), and, finally, Abraham Robinson’s reincarnation of the infinitesimals in the so-called Nonstandard Analysis (of which, I am almost sure, you have not heard)!

What is needed is a kind, humane, and unfailingly correct introduction to a part of mathematics that has had such a long tradition. I believe Thompson’s book does it despite some limitations. I hope more independent learners find this book and find its reading worthwhile. I don’t think school districts will recommend this book for their traditional schools.

The search and study of this book shook me. It made me reexamine my understanding of the foundations of mathematics. I am no philosopher of mathematics, but I have a keen interest in the philosophy of mathematics. Questions about intuition and rigor often make me wonder about the mysterious nature of mathematics.

This book not only rekindled my interest in calculus but also made me explore classroom material to facilitate its understanding. There are several excellent resources for the advanced student to relish, but Thompson’s book, one may hope, can be that lively introduction.

Note on 05 February 2026. I found an excellent critique of this book by Professor R. L. E. Schwarzenberger in an article Why Calculus Cannot be Made Easy. The author explains the complex nature of calculus and its connections to other areas of mathematics. He acknowledges that Thompson’s book was written explicitly for engineering students, for whom the emphasis is on how things work, rather than future mathematics teacher (and, dare I say, mathematicians), for whom the emphasis is on why things work. Schwarzenberger’s paper is extremely well-written and his criticism of Thompson’s book is balanced. This, however, does not diminish my enthusiasm to recommend this as the first book of calculus-1 for high schoolers, but I urge interested students to dig further insatiably. Indeed, like Isaac Asimov says, “Education isn’t something you can finish.”

- ARNOLD: Swimming Against the Tide, AMS: [V.I.] had a surprising feeling of the unity of mathematics, of natural sciences, and of all nature. He considered mathematics as being part of physics, and his “economics” definition of mathematics as a part of physics in which experiments are cheap is often quoted. ↩︎

- Of course, I love discrete mathematics, which is also immensely interesting, tantalizingly difficult, and extremely useful in practice. ↩︎

- We are excluding prodigies like Terence Tao. They know what to learn and how. We don’t need to pick math books for such students! ↩︎

- The first edition was published in 1912! The second edition is available free of cost from the great Gutenberg Project! ↩︎

- “‘What one fool can do, another can!’ — A Simian Proverb” is an excellent example of Thompson’s wry humor. ↩︎

- I highly recommend Gordon Moyer’s article True on the face of it in the amazing, but discontinued, Quantum Magazine. I miss that magazine. ↩︎

- In analysis, we provide rigorous proofs of theorems of calculus. ↩︎