Knowledge has a curse: It grows boundlessly. The Internet grows too. To know something empowering in a way that feels like joy (which is, according to John Keats, a thing of beauty) is what our innate curiosity constantly pushes us humans to do.

Getting such knowledge delivered in a connected world of personalized, AI-driven tools that devour all digitized forms of knowledge should be easy, right? I wish that were the case.

Chemistry is the central science, said Robert Brent in his amazing introductory chemistry book (masterfully illustrated by Harry Lazarus), the Golden Book of Chemistry Experiments. As a homeschooling parent and student of science, I was fortunate to find that book which set us on the path of doing chemistry experiments. These are not just food-color experiments. Although the book has been lightly criticized for not giving safety advice, I believe a certain amount of audacity and luck are required in any experiment. I do want everyone to take appropriate care while conducting chemistry experiments, and profess safety first, but being overly cautious is also not always the right attitude. The Golden Book taught that to me (so did Kary Mullis, a Nobel laureate in his interview after becoming famous for inventing the Polymerase Chain Reaction: At Dreher High School, we were allowed free, unsupervised access to the chemistry lab. We spent many an afternoon there tinkering).

I also found C. L. Stong’s guide, The Amateur Scientist that bears this subtitle:

Experiments and constructions, challenges and diversions in the fields of Astronomy, Archaeology, Biology, Natural Sciences, Earth Sciences, Mathematical Machines, Aerodynamics, Optics, Heat and Electronics. Selected from Mr. Stong’s clearing house of amateur activities, appearing monthly in Scientific American, and expanded with additional information, instructions, notes, bibliographies and postscripts,

from readers.

I also collected several books aimed at a slightly advanced student of chemistry. Among them is Eric Scerri’s The Periodic Table and Its Significance. To me, the idea that the universe is made of about one hundred elements is beautiful and uncanny. The unfathomable and ever-expanding universe is only made of the 100 or so elements? Often, when I talk to my friend Anand Rangarajan (an even more extreme chemistry lover than me), we wonder about how this could be.

Even after reading about these psalms of chemistry (over and over), trying to memorize them, and exploring them visually via the unforgettable Professor Martyn Poliakoff and his periodic table of videos, I still can’t wrap my head around the fact that those are the only building blocks of all matter. Mind-boggling. Period.

Even so, I was looking for a lively introduction to science in general and chemistry in particular. My persistence paid off. My best friend tells me that I can discover great resources about my topics of interest. I guess that is because I believe in serendipity. But serendipity or not, the book that I discovered about chemistry was not on archive.org, the digital library for the world. It was not popular. No forum talked about it.

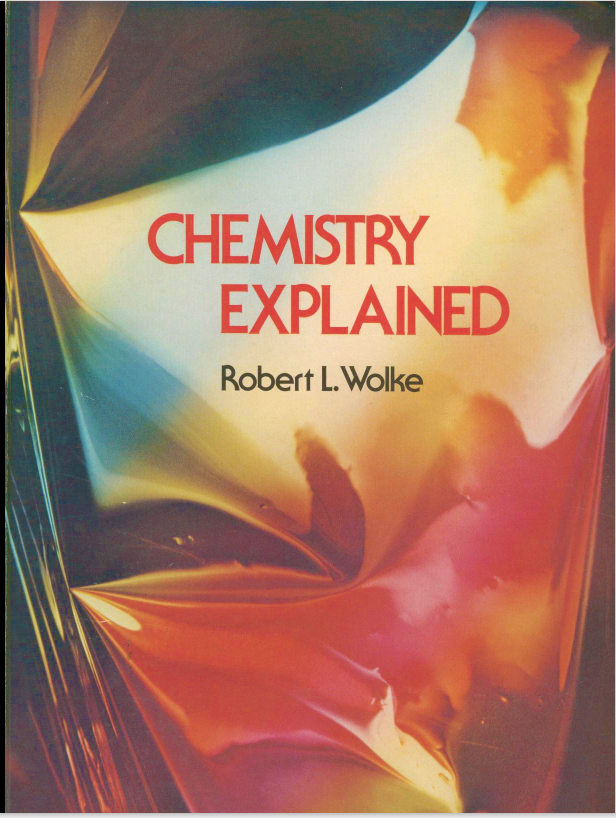

It was a paid book named Chemistry Explained. Although its table of contents was available on the web, I hesitated to pay the $25 it cost at the time I discovered it. The book was also old, of course, not as old as chemistry and Francis Bacon’s invention or proposition of the scientific method (in 1628).

Finally, when I had still not found a suitable book till Rujuta’s junior high school year, I started to get concerned. I finally decided to give Chemistry Explained by Professor Robert Wolke a try. I bought the PDF which cost only $25 for 427 MB of digital data on 576 pages of widely margined paper. It was written in 1979. Professor Wolke had been the professor emeritus at the University of Pittsburgh. He was also the food columnist for the Washington Post.

And I have been duly rewarded for buying this book and making it our chemistry book for Rujuta’s Chemistry-1 course. I discussed it with Rujuta, explained to her that the book is long and we may not be able to get through everything in a “traditional” school year. She decided to give it a try, and I am happy to report that it has been a blast. The author is extremely knowledgeable, witty, and kind. He not only understands chemistry very well (and I don’t need to vouch for that), but also understands how to communicate with students. His style has been remarkably lucid, humorous, clairevoyant (he predicted that in the future computers would be teaching chemistry to you), and highly readable. I haven’t read such a technically superior book with such an effective use of humor for high schoolers. He never waters down the material but never makes it dry and heavy. Every sentence is worth reading and pondering. We have read the first two chapters of the book, but both Rujuta and I are excited to read it every time (and of course do the problems and exercises from it).

Here is a very short teaser of Wolke’s impeccable style and mastery:

First, of course, we have to agree on what we mean by “chemistry.” Chemistry can be defined most simply as the study of (1) what everything is made of and (2) how various kinds of substances interact with one another. The first part of this two-part definition can be called the study of the structure, or composition, of materials. The second part can be called the study of the reactions of materials.

In this book, I’ll emphasize structure and composition more than

reactions, because I believe that as you look around at your environment, you’re more curious about what stuff is made of than in how chemicals react with one another, A longer chemistry course, or a second one, could balance things up a bit more.[Later …]

So the very first lesson to be learned in this business of taking a chemistry course is this: If it doesn’t make sense to you, don’t accept it. Refuse to swallow it. Don’t settle for anything less than understanding. Don’t just memorize it and go on to the next page. Because if you do, that next page is going to make even less sense to you, and before you know it you’ll be trying to memorize everything in this book and everything your instructor says, and that’s a sure recipe for failure.

Chemistry builds upon itself like a pyramid standing on its point. The “heavier” concepts depend on the simpler ones that underlie them. Fail to understand a few of the basic concepts, and you’re in increasing trouble as the structure builds upward while the course goes on. Truly understand each concept as it comes along, however, and you’ll find that things actually get easier as you go, because everything’s fitting together so nicely, without any gaps to make the whole structure totter.

How can you achieve this glorious, shining understanding of each new concept as it comes along? Here’s how.

[And then he gives a 6-point recipe.]

Professor Wolke wrote a few other books (Einstein series) which I will read. He died in 2021. I wish someone (the Internets maybe) convey my gratitude to his family.

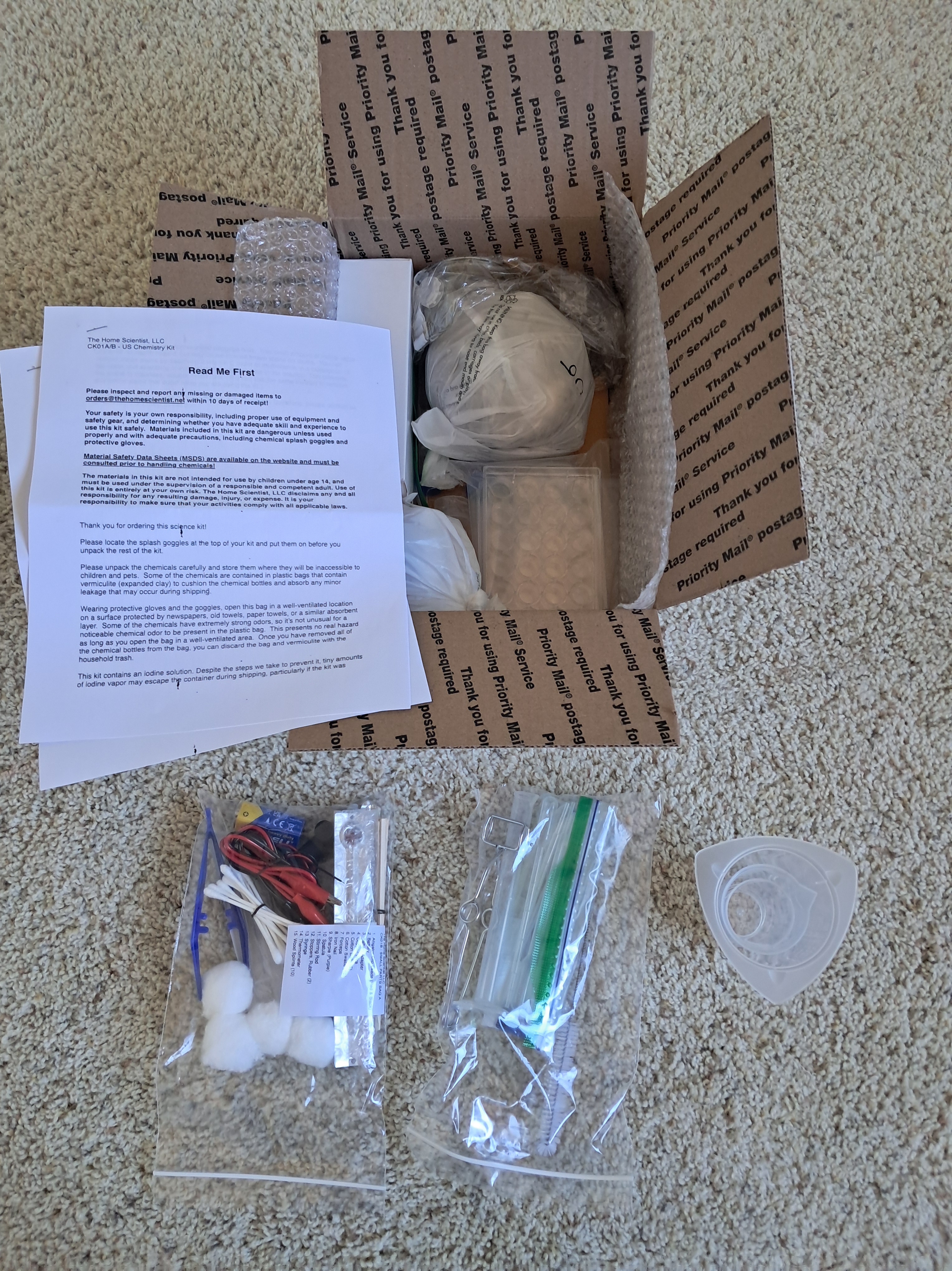

We are going to carry out experiments from another1 Robert’s, Robert Bruce Thompson’s, comprehensive guide to the chemistry lab, published by O’Reilly. Robert Bruce Thompson is also no more. I wrote to his friend, Rick Hellewell, but I haven’t heard back from him; will write to Barbara (Robert’s wife) and Nick Flandrey to pay my homage. Robert’s story is very touching. His zeal to write books for high schoolers is beyond words. We have already ordered the chemistry experiment kit from

I don’t know if Rujuta will grow up to become a chemist [or, in modern lingo, where everyone is so stressed about college majors] or choose a chemistry major in college, but I can certainly say that under the guidance of the two Roberts, our chemistry exploration is going to be a joy forever.

Update: I am sorry, I forgot to write about it before. To set the stage, we are also reading Cartoon Guide to Chemistry by the one and the only Larry Gonick. I still remember Kevin Kelly’s words about Larry (who holds a graduate degree in mathematics; in graduate school he discovered his love for cartoon guides) from the May 1985 issue of the ever enjoyable Whole Earth Review:

Nothing seems to unjam historical facts as well as comic wit, which sends all the monumental stuff down the river, leaving us the odd-shaped key goodies. Harvard mathematics graduate Larry Gonick interrupts his ongoing Cartoon History of the Universe (NWEC p. 566) at 327 Bc. to jump ahead into the briars of America, beginning here with part one.

- Is it purely coincidental that all three authors featured in this post are named Robert? ↩︎